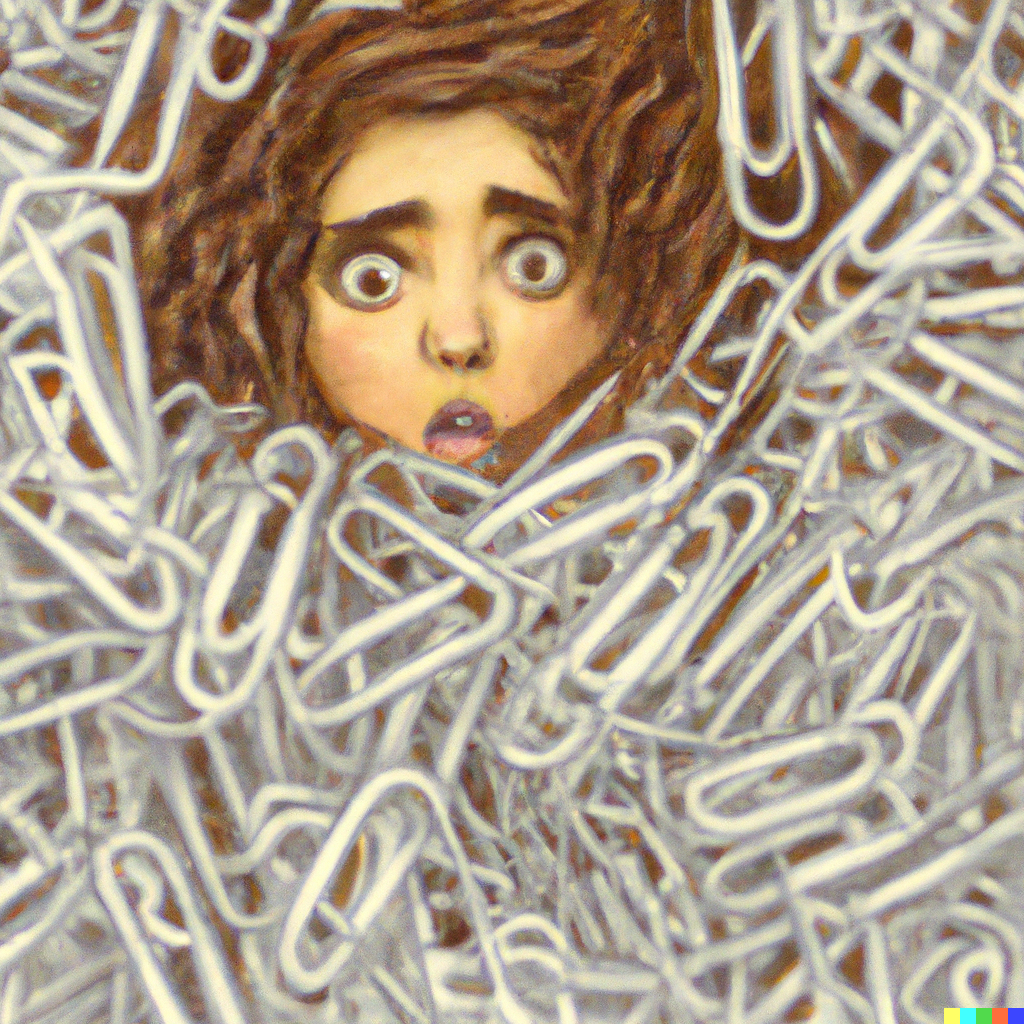

On any given night this week, you would have found me sitting at my desk long past my bedtime, fingers clicking at the mouse erratically, eyes wide and fixed on a colourless monitor full of flickering numbers. No, I haven’t been stressing over PhD work. I have been playing a truly excellent, highly addictive game called Universal Paperclips. Perhaps you know it – apparently millions of people played the game when it came out in 2017, but somehow I missed it (perhaps because I was moving house the month it was released). I have been making up for lost time.

The blame for my present mania lies with Tom Chivers, whose book The Rationalist’s Guide to the Galaxy: Superintelligent AI and the Geeks who are Trying to Save Humanity’s Future I am currently reading. He recommends the game (with a warning that his whole office lost a working day to it) whilst describing the inspiration behind it: a thought experiment concocted by philosopher Nick Bostrom, one of the aforementioned Rationalists. (Bostrom wrote the hugely influential Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies which is on my to-read list).

The paperclip-maximiser concept goes something like this. An artificial intelligence is programmed to make paperclips. With this as its sole aim in life, it will do anything it has to do to make more paperclips. This might involve expanding factories, buying up the competition, streamlining production, maximising profits through advertising and investment, upgrading itself so that it can innovate further, inventing a way of turning all matter into paperclips, expanding across the globe/galaxy/universe to enhance matter collection, doing something about those pesky humans who want to turn it off…

It is a cautionary tale that highlights the importance of ‘value alignment’. The AI has not been programmed to value human life, or anything other than paperclip maximisation, and it has not been given any limits on its use of resources. So it will have no qualms about using all the matter in the universe, including the matter contained within its human creators, to maximise its paperclip production.

Chivers highlights a similar story which uses magic instead of technology: the tale of the sorcerer’s apprentice (familiar to most of us as Mickey Mouse in the Disney film Fantasia). The sorcerer’s apprentice, tired of doing his chores, enchants a broom to fetch water for him. As the broom repeatedly carries out this instruction and the room begins to flood, the apprentice realises he does not know how to stop the broom. The broom, just like the paperclip-maximiser, is relentlessly pursuing its goal without appreciating that the results are detrimental from a human perspective. The apprentice takes an axe to the broom, but the pieces, still endowed with their one goal, become new brooms which continue to fetch water. Eventually the sorcerer returns to break the spell, and warns that only a master should invoke powerful spirits.

Even a master sorcerer, or programmer, might get it wrong. As we develop AI systems it is important to discuss the issue of how we instil human values. This is no simple question, because what values are these? Human values look different across periods of history, across cultures and across individuals. They even look different across an individual’s lifespan; which of us hasn’t grappled with ethical concepts and occasionally changed our mind? Humanity is a wildly imperfect teacher. AI has already begun to replicate our biases, such as racism and sexism, by learning from historic data of faulted human practices (I recommend the documentary Coded Bias for more on this). Do we tell AI: “do as I say, not as I do”? And how do we agree what to say?

While you ponder these issues, I suggest you indulge yourself and have a go at Universal Paperclips. It gives you a taste of being not so human (compounded, if you like, by eyes-glazed-over weariness) and of being compelled by one arbitrary goal. It’s enormous fun.